IMAGE: KAITLIN BRITO

While some of her neighbors may have thrown up their hands in frustration at the persistent presense of camps in Laurelhurst Park, often cited as a symbol of the city’s homelessness crises, Jan McManus, a longtime Laurelhurst resident, saw them as an opportunity for change.

A call for proposals of alternative housing issued by the Joint Office of Homeless Services was the perfect opportunity. “I had the skills and experience to try to address that,” says McManus, a retired social worker. Christine Tanner, a retired nurse and academic with a history of grant writing—and McManus’s longtime friend—felt a similar drive. Together, they gathered contacts in the nonprofit world to form the board for WeShine (Welcoming, Empowering, Safe Habitation Initiative with Neighborhood Engagement), incorporated in May 2021, and got to work.

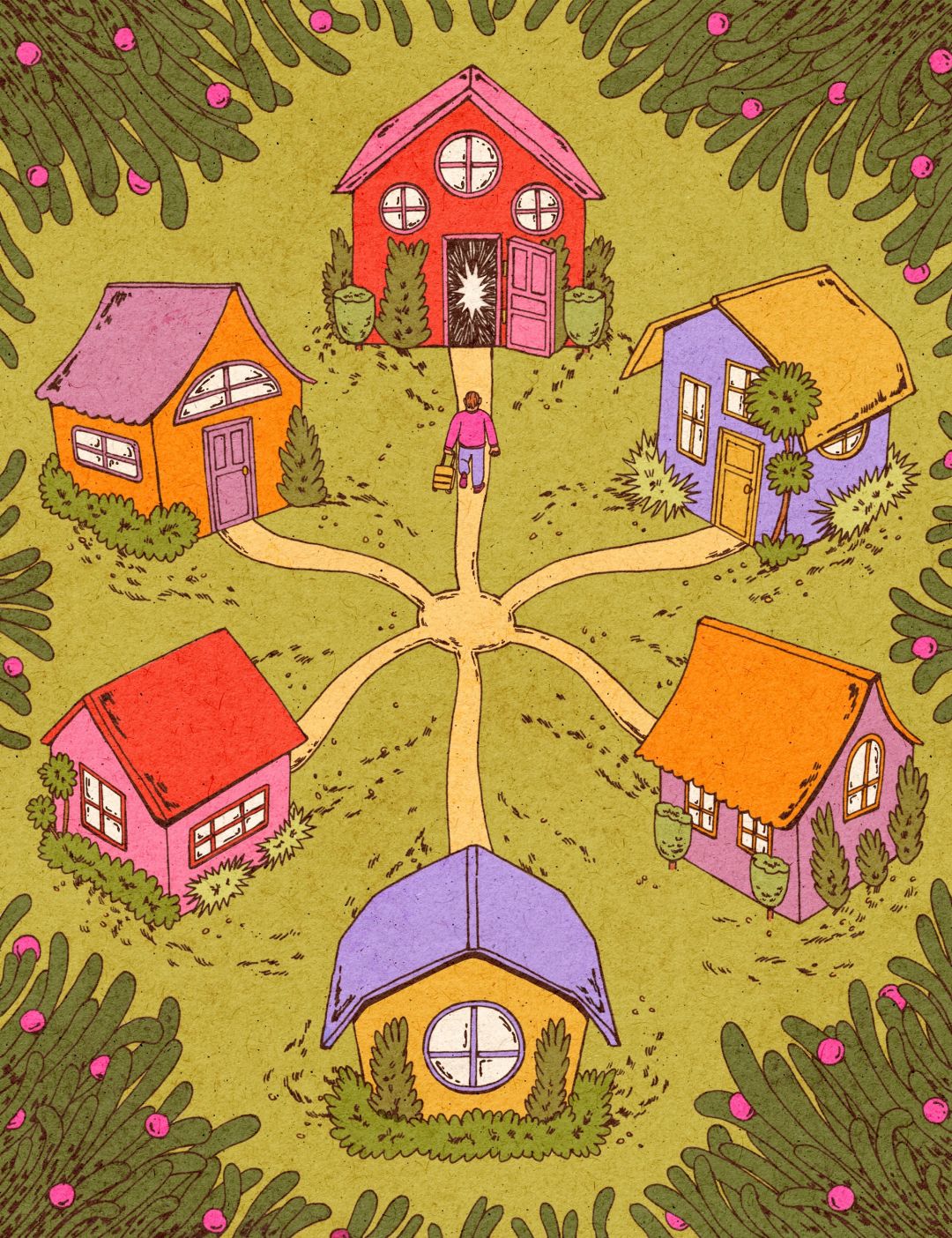

A little over a year later, WeShine’s first microvillage opened in Northeast Portland’s Parkrose neighborhood, a 10-pod village built on private land, in the Parkrose Community United Church of Christ’s parking lot.

WeShine’s microvillages are an alternative to congregate-style homeless shelters and are smaller than the city’s Safe Rest Villages, which aim to house roughly 50 people apiece. The smaller size, they say, can fit more easily into neighborhoods, and also help foster community and give villagers agency over their housing, factors that were found by a recent Portland State University study to be instrumental to pod-village success.

Denis Theriault, a spokesperson for the JOHS, notes WeShine’s research-backed adoption of peer support. A WeShine village is supervised by a live-in village life coordinator—someone who has experienced houselessness themselves, who helps the community make day-to-day decisions on things like curfew, allowing guests, and how the refrigerator is organized.

WeShine prioritizes BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ applicants, citing the PSU study, which found just 17 percent of residents in existing villages identified as BIPOC, though people of color make up 40 percent of the city’s homeless population. The application process works to remove barriers to housing solutions, but low-barrier does not mean a free-for-all. “Good neighbor” agreements—drafted with input from the community—are signed by all villagers, and current villagers can review new applications.

Ultimately, the goal is to add to the options available for those seeking shelter. “There’s not homogeneity in the homeless population. People need different things,” says Tanner.

WeShine currently has funding for a second village and is in talks with four additional sites. “We think there needs to be 100 of them, but what we personally think we could pull off—over a period of maybe five or six years—is about 10,” says McManus.

Aside from providing shelter, she hopes the villages can inspire a change in attitudes surrounding homelessness: “What I can do is give people something to be for—another approach.”

Portland Monthly solicits nominations for the Light a Fire awards, our annual nonprofit honors, every summer and makes selections with the help of a panel of volunteer advisers from the local nonprofit community.